Ending Violence against Vulnerable Groups in Kano State

Charles Uche Esq

Few of the notable deficiencies of the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act of 2015 are its inability to criminalise spousal rape and provide adequate protection to persons living with disabilities – even though this was (sparsely) addressed by the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act of 2018. Sadly, both laws are inoperable at the subnational level without first being enacted by the Houses of Assembly of various states.

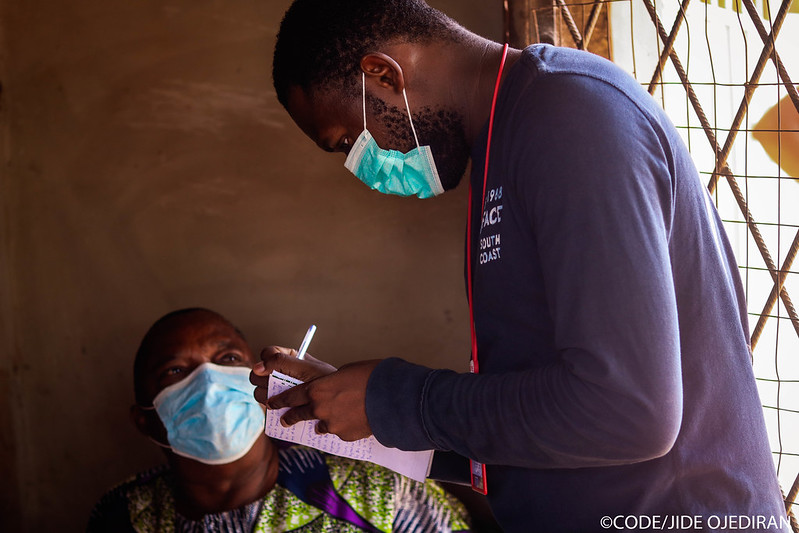

On the 2nd and 3rd of February, 2021, I was in Kano state to implement a project sponsored by the Canadian High Commission in Nigeria. Our team was to train 30 young women and men gender-activists on advocacy tools towards ending gender-based violence through the enactment and/or adoption of the provisions of a Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Law in Kano state.

A story was told of two young girls below the age of 14 who were abused by an affluent man in their neighbourhood. The man is attempting to bribe the father of these 2 underage girls with N500,000 so that the court case can be terminated. Another story was told of a woman who was prematurely forced into labor and childbirth due to spousal battery. A lady told her story of how she had to quit her dream job because of sexual harassment from her boss at the workplace. Another story was told of an underage girl who was gang-raped by known men and who used stigma to pressure her into silence. There are countless stories of forced child labour and prostitution and child marriages.

You see, these are what one may describe as a “tip of the iceberg”; just some troubling stories of the ordeals and violence women and girls go through in Kano state and across Nigeria as a result of inter alia inadequate or lack of effective policy and institutional frameworks that carter for the actualisation of women’s right. In seeking for justice, I discovered that many women or people have preferred to lay their complaints to the Islamic Police: Hisbah Corp which has no legal power to prosecute rape cases and where matters are often settled through mere mediation rather than the Nigeria Police Force which has the broad statutory powers to prosecute virtually all forms of criminal cases, subject to to powers of the Attorney General.

This 2-day workshop I learnt about young female activists; brave and resilient women; some victims with horrific stories of sexual and gender-based violence – and many of whom have been denied justice deliberately and otherwise.

The institutional performance of State agencies that are responsible for ending gender-based violence and protecting women’s rights was rated poor. “The Police have no shelters for victims and would not want to be burdened with such cases. There have also been reports of police officers taking advantage of survivors and women in disadvantaged situations,” a participant at the training noted. Another woman emphasized that police officers often blame the victims or pressure them to go and settle their “domestic affair”. These and many more engenders the distrust and widens the divide between women, victims and the Nigeria Police Force and their ability to access justice. This distrust is being capitalised on by the Hisbah, with its prosecutorial controversies and limited role in criminal justice on the broader scale.

In Kano state, there is only one sexual assault referral centre (SARC) which “ideally” is supposed to function as shelter, forensic evidence extraction point (to be used in trial) and carter for the general rehabilitation needs of victims of sexual violence. This centre is grossly understaffed, under-equipped and underfunded. Kano is the 20th largest state by land mass; perhaps, the second most populous state after Lagos state and has 44 local government areas and hundreds of villages in remote areas – how can women and victims living in marginalised, grassroots communities access the services of the SARC when the facility can barely carter for the victims within its immediate sphere of operation.

Just like the Anti-Domestic Violence Law of Lagos State of 2007, the VAPP Act also provides for the protection of survivors of domestic violence; provides them with opportunity to acquire skills in any vocation and access micro credit facilities. The VAPP Act ultimately seeks to prohibits many forms of violence on persons in private and public life and its domestication in Kano state has been a subject of immense controversy – and have inadvertently faced setbacks in its legislative enactment – as some quarters have linked the law to the realisation of LGBTQ rights in the state or have simply cited cultural or religious reasons as to the hitch – meanwhile, women continue to be susceptible to all forms of abuse and violence within the state with little or no recourse.

The socio-legal debate that have been generated due to the VAPP Law and its adaptation to local context has led relevant government and private stakeholders to reach a middle ground which is allegedly the extraction of notable “contextually-agreeable” provisions of the VAPP Act and infusion into the Penal Code; a harmonisation exercise that has subjected the Penal Code to an amendment process and which would hopefully lead to the manifestation a more inclusive Penal Code Law that broadens the protection and realisation of women’s right in the state. May I state here that I’m sceptical about the outcome of this process – “when” it eventually arrives.

Furthermore, on December 4th, 2018, the Kano state Governor signed the “Law for Persons with Disability”. However, unlike the federal version, the state law didn’t provide for a Commission that would inter alia represent and further the causes of persons living with disabilities (PLWD); did not provide for sanctions in cases where the rights of PLWD are infringed upon; did not provide a transitional period where all public buildings must provide PLWD-friendly entry and access points; did not provide affirmative action in public employment for PLWD, and so forth. All these policy gaps and many more exist for a group often neglected by society, who are more vulnerable to all forms of violence and abuse, and whose access to justice is much more cumbersome. In fact, the law can simply be deemed a theoretical declaration of rights, perhaps, to hastily fulfill promises or quell international or local pressures. The law and its current amendment process is piloted by the Office of the Secretary to the State Government. While this may be okay at the interim, for sustainability and inclusivity sake, this cause and interests should be coordinated by a ministry of government in charge of social development or special duties.

In conclusion, this article has attempted to analyse and portray policy gaps that exist and suggested ideas towards the protection of vulnerable groups and their rights thereof in Kano state, proffering solutions below. While I support the enactment and domestication of laws to suit local contexts in line with our federal system of governance, these legal and legislative adaptations must not be in aberration of fairness, equity and comprehensive multi-stakeholder engagement, foremost of which are Women groups, Community based groups, Civil Society Organisations and PLWD groups.

Here are some policy recommendations which may be considered and adopted towards ending all forms of violence against women, girls and PLWD in Kano state and across Nigeria:

- The state government should enact and implement the VAPP Law and/or adopt a utilitarian approach towards the harmonisation of the VAPP Act and Penal Code suitable for the local context, reached through broad, multi-stakeholder and cross-sectoral consultations.

- The government should enact and implement the Child Rights Law and/or the Child Protection bill.

- There should be a precise Action Plan to End Gender Based Violence within a definite time frame in form of a policy document, highlighting the role of various stakeholders, amongst other things.

- There must be gender responsive budgeting in appropriation laws, especially through the budget of the Ministry of Health and/or Women Affairs.

- There must be establishment and sustainable funding, equipping and professional staffing of more Sexual Assault Referral Centres across the state through annual budgets of the Ministry of Health

- Implementation of a robust database of sexual perpetrators.

- Increased sensitization on mainstreaming gender sensitivity and equality in public and private life embarked especially by public institutions as a matter of policy.

- There should be enhanced special desks at police stations manned by trained, empathetic professionals; and establishment of special courts for sexual related offences to protect identities and ensure speedy, justiciable trials.

- There must be an amendment of the Persons with Disabilities Law of Kano state to provide comprehensive protection of PLWD by addressing the issues and policy gaps raised in this article.

Note: This article is not an attack on the institutions of Kano state and should be read with objectivity and with the analytical and solution-driven lens of the writer towards ending violence on women and girls in Kano state and across the country.

We were certain that the current COVID-19 health emergency was worsening

We were certain that the current COVID-19 health emergency was worsening